How To Train For Cross Country: A Comprehensive Cross Country Training Plan

Here’s the deal – most articles about cross country training plans aren’t that helpful. The training suggestions are too general, the coach doesn’t explain the “why” behind the workouts, and they don't, therefore, end up clearly explaining how to train for cross country.

In this article I’m going to explain exactly what a summer cross country training program should include, with a simple rationale for each workout. So, if you're looking for some help sorting out the finer details of how to coach cross country, you're in the right spot.

Next, I’m going to explain how cross country running practices should be structured. This includes a dynamic warm-up for runners (rather than static stretching), a workout or an easy run with strides, followed immediately with post-run strength and mobility exercises. Along the way, I’ll teach you three crucial concepts that’ll likely be new to you.

Finally, I’ll explain the three most common mistakes I see coaches (and athletes) make in cross country training.

Before we dive in, I want to be clear that the following is for coaches, yet this article will be informative for anyone passionate about cross country (athletes and parents alike). If you’re a high school cross country runner, check out my 10 Essential Tips for Cross Country Runners. Parents will want to read A Simple Parent's Guide to Cross Country. For coaches, the following is going to give you a clear plan for your program in the next cross country season. (And coaches, if you're looking for training schedules, here's a cross country weekly training schedule, with 5 weeks worth of schedules to get you started.)

Ready?

Let’s go!

The Car Analogy

Build the Aerobic Engine

The best cross country training plan has its foundation in sound exercise science. While I have a master’s degree in Kinesiology and Applied Physiology, you don’t need one to help your runners race to their potential. But you do need to understand one key point about 5000m cross country races: they are fueled by the aerobic metabolism.

Let me explain...

Think of a high school runner’s body as a car. While the analogy isn’t perfect, it can help you understand some of the keys to consistent improvement.

Distance runners need to build their aerobic engines if they want to race faster. And the reason is simple: what’s known as the aerobic metabolism contributes the majority of the energy that a high school runner’s muscles need to power them around the cross country course.

Take a moment to consider the following table:

There’s a lot going on in this table, but you only need to take away two essential points.

First, every distance a high school runner races – from 5000m (5k) all the way down to 800m – is more aerobic than anaerobic – in other words, the energy system that requires oxygen is doing more of the work than the energy systems that don’t.

Second, the aerobic contributions to performance increase as the distance gets longer, with 5000m cross country races being 95 percent aerobic.

It’s these two points that shape effective training programs for distance runners: your runners need to focus on building their aerobic engines throughout the year because races ranging from 1600m to 5000m are primarily powered aerobically.

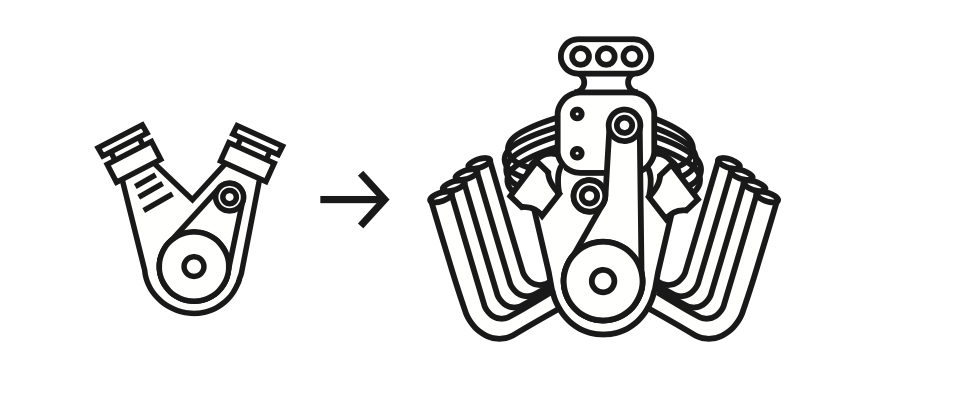

To use our car analogy, when you give athletes the right aerobic workouts, they’ll transform their four-cylinder engine into a V-6.

Strengthen the Chassis with Running Specific Strength Training

A car’s chassis is the frame that holds the engine, as well as the other machinery, that makes it move. Using a car analogy, the athlete’s bones are the body’s main structure, and the muscles and tendons, as well as the ligaments and fascia, also form part of the “chassis.” Strengthening each of these is crucial to staying injury-free.

If a coach can help an athlete stay injury-free, with the rare missed day or two here and there, the athlete will race fast, and have fun.

Conversely...

An injured athlete who misses practice and doesn’t get to race isn’t going to have fun.

This is why the best coaches keep the concept of “injury-free” training at the forefront of their minds, and make it the primary goal of a six-month training plan.

The next reason to focus on strengthening the chassis isn’t as obvious.

Young athletes will “build their engines” faster than they can strengthen their chassis. My friend Mike Smith, who coached at Kansas State University and now coaches at West Point, introduced me to this concept when I was coaching at the University of Colorado.

“Metabolic changes occur faster than structural changes,” he explained. And that’s why he had his college athletes do so much work to strengthen all the components of their chassis, work that I had never seen before.

For high school athletes, who are often coming into running with modest athletic backgrounds, their engines can improve dramatically in just a few months. That means they need to spend a significant amount of time strength training, so that both their engines and chassis improve at roughly the same rate. This does not mean they need to go to the weight room, rather they need to follow my progression of post-run strength and mobility routines that start with body weight exercises.

Here’s the deal...

High school runners need to do chassis strengthening work every day that they run.

This is such a crucial part of a sound cross country training plan that I have a separate article, with all the videos you need for your athletes: The Best Strength Routines for Runners.

Let’s move on to the final part of the car analogy...

Rev the Engine Most Days by Running Strides

Staying with the car analogy, it’s important that your athletes “rev the engine” most days by doing strides. A stride is simply a quick, short sprint – anywhere between 70m and 150m – that’s faster than a 5k race pace. There are two simple reasons cross country runners must do strides.

- Your runners must practice running faster than race pace to internalize that “challenging but doable” effort so it feels realistic when the gun goes off.

- They must regularly rehearse speeding up – or “changing gears” – if you want them to do the same thing in a race.

One of the biggest mistakes I see coaches make is that they don’t have athletes doing strides on the first day of cross country practice.

We can easily fix that!

Just follow my Progression of Strides for Cross Country which will safely have your athletes running faster than 5k pace in the first weeks of practice. Consistency is key when it comes to strides. So long as athletes show up to most summer training sessions, they’ll be running 800m or even 400m PR pace for short strides when the cross country season starts.

It’s worth saying this once more: You’ve got to assign strides the first day you meet your athletes, and you must make sure you’re safely progressing the intensity of the strides over the course of the summer so that your runners are comfortable running 800m and even 400m PR pace when the season starts.

If you’ve read this far, you’ll want to download the three chapters on the car analogy from Consistency Is Key: 15 Ways to Unlock Your Potential as a High School Runner. To get those chapters simply share your email. I’ll never send you spam – I'll just send you great workouts and useful advice that matches the phase of season you’re in.

Let’s move on.

The Four Elements of Each Cross Country Practice

1. Warm-up

2. Workout or easy run

3. Strides

4. Post-run work. Note that on some workout days we won’t do strides.

Warm-up

Let’s start with what we’re not doing. We’re not doing static stretching, then running. Instead, we’ll do a dynamic warm-up for runners, a warm-up that has our body moving in all three planes of motion.

Let’s get technical about this point for 20 seconds...

Running is primarily a “sagittal plane” movement – the forward-backward plane. What’s important if you want to stay injury-free is to also move in the other two planes during your warm-up. The “transverse plane” is the body’s rotational plane, and the “frontal plane,” – is the body’s side-to-side plane. These planes are typically ignored by runners, but that’s a problem. Even though running is primarily a sagittal plane activity – moving forward – high school runners are well served when they maintain the athleticism that they bring to XC from other sports. In the same way a basketball player or soccer player moves in all three planes of motion in their warm-ups, we want runners to be decent in all three planes of motion as they warm-up.

My experience in 20 years of coaching is that...

Injuries greatly decrease when athletes commit to doing a dynamic warm-up for runners that has them moving in all three planes of motion, before every run or workout.

There are several ways to do this. Your athletes could do leg swings and the lunge matrix, which will take a total of five minutes. This was my recommendation for over a decade, and it’s a good one, but today I have a better one. Check out my 5-Minute Running Warm Up if you’re pressed for time.

The best dynamic warm-up a runner can do is Jeff Boelé’s, which you and your athletes can get for free on your phones. This warm-up is specifically designed for competitive runners. Thousands of high school cross country runners use it, and they swear by it. Once your athletes learn it, it will take a bit over 10 minutes. Although 10 minutes might seem too long for a warm-up, I can assure you it’s worth it.

A proper dynamic warm-up before every cross country run is crucial for high school athletes to stay injury-free.

To get Jeff’s warm-up on an app on your phone, simply share your email. And you can share this link with your athletes so they can do the same.

High School Cross Country Workouts

After the warm-up, we’re either going to do a cross country workout or an easy run with strides.

There are two types of workouts – challenging aerobic workouts (which build the aerobic capacity/build the aerobic engine) and race pace workouts. We’ll use five different challenging aerobic workouts in our training, and a handful of race pace workouts.

Challenging Aerobic Workouts

I go into more detail about these workouts in this article: 5 Must-Do Cross Country Workouts. Make sure to check that out. Here’s a brief overview of these five must-do aerobic workouts.

Note that the order below is the order in which athletes should learn the workouts. One of the key elements in my system is that athletes need to “run by feel.” These five workouts do just that, starting with the long run.

Long Run

The long run is one of the best ways for athletes to develop their aerobic engine. We’ll do strides in the last 20 minutes of the long run, and we’ll start the off-season using minutes and not miles for the long run assignments.

Fartlek Run

Fartlek is a Swedish term that means “speed play” and there is little doubt that fartlek training is a simple and effective way to gain fitness.

A “true fartlek” is a workout where the athlete is oscillating between multiple paces. We’ll simplify things and go back and forth between two efforts. We’ll have an “on” portion and a “steady” portion. The crux of our fartlek workout is that the “steady” portion is faster than your athlete’s easy run pace.

Again, check out the 5 Must-Do Cross County Workouts article discussing how to assign a fartlek workout. Fartlek workouts are underutilized by my coaches; I don’t want that to be you, so make sure you take the time to educate yourself on how to assign these effective workouts.

Progression Run

Progression runs are simple and extremely effective. Plus, they’re fun! We’ll typically use 5-minute and 10-minute chunks for runs that range in duration from 15 minutes to 30 minutes (though older athletes could do 35-and 40-minute progression runs).

A 20-minute progression run is written as: “10 minutes steady; 5 minutes faster, but controlled; 5 minutes faster, but controlled.”

Athletes should end the workout saying, “I had 3 more minutes in me at that final pace, no problem, and if I had to do 5-6 more minutes, I could have.”

A progression run can replace a long run in the middle of the season.

When a coach wants to get in a challenging aerobic workout, but wants the athlete to spend less time on their feet, and have their legs feel fresh 48 hours after the workout, a progression run is the perfect workout choice.

Aerobic Repeats

Aerobic repeats are longer repetitions – 4 to 6 minutes – that are as fast as an athlete can run without producing any lactate. Unlike a fartlek workout, you won’t have your athletes run “steady” between the repetitions, but rather they’ll run at an easy pace.

Athletes love this workout, yet you need to do a couple fartlek runs and a couple progression runs before you progress to this workout.

30-90 Fartlek

This fartlek workout is much different than the traditional fartlek workouts we’ll do during the year.

Athletes run 30 seconds at 5k cross country goal pace then run 90 seconds at an easy pace. After a few repetitions of this, the athlete can speed up the 90 seconds and see if they can run a bit faster, though it’s not mandatory that they run steady (as it may not be realistic for them to run 5k cross country goal pace for 30 seconds and run steady for 90 seconds).

If an athlete is having an off day, they need to keep the 30 second portion at 5k race pace, then simply run easy for the 90 second portions.

This is another workout that athletes look forward to as it’s fun, and, the overall workout is a bit shorter.

There are two concepts that underly all of these workouts, which I explain in detail in Consistency Is Key.

1. Running by Feel

It’s crucial cross country athletes learn to run by feel, and these workouts teach that skill.

2. Farther or Faster (or Both)

Athletes must finish these workouts saying, “I could have gone farther” or “I could have gone faster.” For long runs, the athletes must finish saying they could have done both.

Race Pace Cross Country Workouts

During the season we’ll obviously have to do workouts at 5k pace, and then practice speeding up. There are a handful of workouts I use in the XC Training System, one of them being the 300m repetitions with a 200m float. If you want to learn more about that workout you can watch this video.

Strides

We’re running strides in the last 20 minutes of long runs, and we’re running strides in the last 15 minutes of every easy day.

“We’re doing strides during the run? I thought strides came after the run.”

Trust me on this: When strides are something you assign your athletes to do after a run, they often don’t get done. Plus, running with great posture when your runners are a bit fatigued reminds their body (and mind) that they’ll have to do the same in a race.

We don’t do strides following the challenging aerobic workouts, but we’ll get in strides every other day that we run.

Following every workout or run we go immediately into...

Post-run Strength and Mobility Exercises

We’ve agreed above that your runners must strengthen their chassis if they’re going to stay injury-free. This is the time in the training session where we do this work.

It's important that – if the weather allows – we go immediately into this work

All four of these elements – Warm-up, Workouts, Strides, Post-run Work – need to be done back-to-back so we can “extend the aerobic stimulus.”

What I mean here is that we simply want to keep their heart rate up as long as possible. If there are no breaks between the warm-up, the workouts or easy run, and the post-run strength and mobility work, we’ll get a long aerobic stimulus, but with a moderate amount of running.

This is a key reason why my system keeps athletes injury-free and helps them run PRs: They get as much or more aerobic benefit from the training days as their competitors, but they do so with less running.

Now, to be clear, I think upperclassmen can run significant volume (mileage) if: (a) they are fired up to run more volume, and; (b) they’ve safely progressed over months and years to bigger volume. But younger runners can run fast with a moderate amount of running so long as they don’t take any breaks between the warm-up, the workout, and the post-run work.

Doing post-run strength and mobility work also helps athletes “build their attention span for hard work,” another concept in Consistency Is Key. Post-run work is hard, and it’s especially hard after workouts. Yet when an athlete can focus and get through this workout with a high level of energy, they’re going to be able to stay focused for both race pace workouts and in races.

Now you have a cross country training plan that will work in any environment.

Common Mistakes That You Can Easily Avoid

I want to wrap up by sharing the top three mistakes high school cross country coaches make with this plan, and help you avoid making them.

1. Not having athletes run strides the first week of training.

2. Not having a progression of strides that ends at 800m pace (and even 400m pace) as soon as possible.

3. Not being focused on the “extending the aerobic stimulus” each training session.

You can take care of the first and second items by reading the Progression of Strides for Cross Country article. Once you do that you simply need to assign strides the first day of practice, and make sure that the athletes who regularly attend practice are moving towards 800m rhythm as soon as possible. Strides are fun and within a couple of weeks the athletes will look forward to doing all the strides that you’re assigning each week.

It will likely take some time to get your athletes to buy into doing post-run work with good energy immediately after training. They’ll be fatigued after the running portion, yet if you can get them mentally prepared to do post-run work immediately after training, they’ll get a much longer aerobic stimulus from a moderate amount of running.

Again, my system keeps athletes injury-free and gets them ready to run PRs, in part because of this crucial modification in training. (Note: there are times when weather will prevent you from having your athletes finish a run or workout and go immediately into the post-run work – that's fine, so long as you embrace this approach and do it as often as possible).

The Final Point...

You now have a framework for training cross country athletes, and that’s a great start. What you don’t have is...

XC Essentials Training: Workouts, videos, PDFs.

- 4 weeks of training for six different levels of athletes. This is everything you need to start summer cross country training.

- Progression of strides PDF.

- Post-run routines PDFs.

- Jeff Boelé’s videos – including the warm-up.

- My videos – including videos of all the post-run work.

- Consistency Is Key for Cross Country video – this concise video lays the foundation all workouts and training in the XC Training System. You don’t want to miss this one.

I’ll send you access to the videos and PDFs when you share your name and email. I’ll never spam you, but rather I’ll send you useful workouts and training advice.

XC Training System

If you want to take your program to the next level, take some time to check out the XC Training System. It’s a game changer, and it’s helped both veteran coaches and relatively new coaches take their program to the next level (and yes, for some coaches that has meant using the XC Training System and going on to win a state title in cross country).

Check out the XC Training System

Check out the XC Training System